I retired from the UGA departments of romance languages and women’s studies in 2011 after a lifetime of studying and teaching. And for all of my life, I had associated my academic achievement with my Russianborn father. He was the one who graduated from Columbia Pharmacy School in 1926, three years after arriving in the United States; who spoke French; who had traveled the world and studied in France and Switzerland. I always remembered my mother in the role of a very proper 1950s housewife who wore white gloves and a hat to the grocery store.

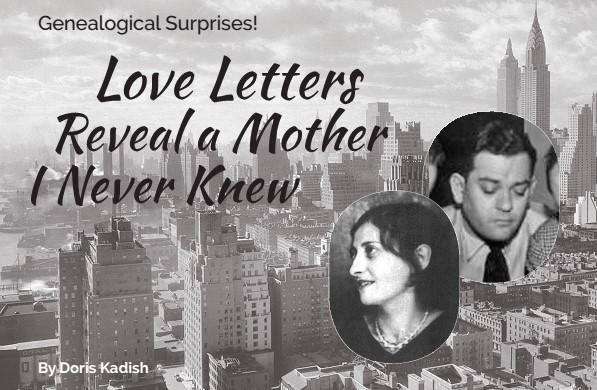

All that I had known about my mother changed after I retired and discovered a treasure trove of old love letters to her in my sister’s Albany, New York, attic. Amazingly, my mother, Ethel Richman, had had a lover who would become world famous in literary circles. The letters, and all the subsequent research that flowed from them, cast a whole new light on who I thought she was, and her influence on me.

Her family were Russian immigrants who had settled in Savannah in 1892, and whose life revolved around the orthodox synagogue. A spirited, intelligent girl in the 1920s, Ethel Richman rebelled, creating a break with her large extended family that was never entirely mended. The societal and religious strictures for women and girls at that time were vast; for example, females were relegated to the balcony during the synagogue service, hidden from view behind a curtain. Growing up, I knew she had moved to New York City from south Georgia at age 23 and lived independently in bohemian Greenwich Village until 1935, when she married my father, Eliahu Young (Youngstein). But, as an adult, I had hardly known her or her past life. She and my father died in 1966 in an automobile accident when I was 26.

During my childhood, we lived in a rural area outside the city while my father commuted to his bookbinding business. It was a quiet life for my parents and my sister and I, centered on reading, conversation, and listening to opera on the radio. But as I reached adolescence, this life became stifling and alienating. I fell passionately in love, but he was not Jewish.

My parents were secular Jews, but still my mother broke up the romance behind my back in what I considered a very devious way. I was hurt and resentful for many years. And then she died so early, we didn’t have time to repair our relationship.

The family enjoyed reading together. Doris, left and sister Myrna, right.

After they died, I followed a traditional path, graduating from college in June 1961 and marrying a month later. I had three children while attending graduate school, ultimately divorced, and got my doctorate in 1971 at age 31. Upon retirement, I now had the time to look into my family history, sorting through dusty boxes of old photos and papers. And what a surprise to find 33 love letters sent to my mother by a Philip Greenberg from 1928 to 1931.

They were so passionate I didn’t even want to read them at first, full of declarations of love and poetry. He told her he wanted to be a writer; he bared his soul; he implored her to join him. I couldn’t imagine the circumstances; the person who inspired the letters was a stranger to me.

I had no letters from my mother to Philip, but his to her showed a man who was deeply intellectual. In fact, he seemed to mirror my father in many ways. They both avidly read the serious literature of the times, and both were deeply admiring of Thomas Mann and his book “The Magic Mountain.’’ I remember feeling so proud when my parents said I was old enough to read it.

But then months went by and I thought no more of Ethel, Philip or Magic Mountain until my nephew David Barnet discovered unexpected facts about who Philip Greenberg really was. I began to do research and looked closely at the census, court, and immigration records David had found. Many surprises were in store for me!

| Such Longing |

Philip Greenberg had arrived in America from Russia in 1922 as Fevel Greenberg. As an aspiring writer in the late ’20s, he wrote to my mother that he was going to publish under Philip Rann so as not to jeopardize his employment. He wrote a few of his letters to her from New York City and ultimately mostly from Portland, Oregon, where he had moved after having apparently been fired from the Hebrew School in Savannah. Piecing together information in the letters with some research and personal interviews in Savannah, I was able to determine that several prominent Jewish intellectuals found themselves in Savannah in the early 1920s. One, Mordecai Grossman, had probably hired Fevel/Philip to teach Hebrew. Internal politics at the Hebrew School appear to have driven Grossman, Philip, and the other Jewish intellectuals away; they were progressives, particularly regarding race, and too much ahead of their times.

In reading his letters to my mother, it was clear he was a passionate man who could eloquently express his deep feelings.

“Ah, Ethel, how lonely I am for you. More and more I realize my misery. Is there no way out? Must we be separated? At night, in those dark heavy hours of sleepless brooding, I recall all the tender blissful moments we had together. I remember the evening when I first asked you to kiss me, and the gleam in your eyes, that charming hesitation, the moment of suspense before the leap. Those everlasting kisses, those hours of blissful intimacy, pregnant with tenderness and supreme understanding.

My blood calls for you. You have permeated my being like some subtle elixir, some rare alchemy of yore!”

But what stood out most to me was Philip’s dominant, authoritative voice. From his very first letters to Ethel I caught a glimpse of this character. His declarations of love were often coupled with reprimands and orders concerning Ethel’s future conduct. In the earliest letter he told her that the pictures she claimed to have sent never arrived. In the future she must get the street number right, buy a larger envelope, and stick to their arranged schedule of her writing every Thursday.

Still, he seemed to be quite enamored of my mother. He spoke of their “absolute, made-for-each-otherness. I have put you on a pedestal, and if I believed in God, I’d pray fervently to him and ask him that you should always remain on that pedestal, so pure, lovely, and ravishing.”

Why didn’t Philip and Ethel marry? Her letters must have indicated a desire to move to New York and for him to return there. His letter of Dec. 19, 1930, provided a five-page summary of why he could not. Money figured prominently. He told Ethel: “for me to come to New York would be utter madness. I cannot live shabbily. I cannot write when my mind is filled with financial worries.” He had saved half his salary for three years to become a writer, not a husband.

| Separate Paths |

While I sadly have no letters of my mother’s, his indicate she had determined to leave her provincial community and orthodox Jewish family and move alone to New York, something her family deeply disapproved of. He takes credit for it:

“Surely your relationship with me helped you to find yourself and to escape the provincial pit and over that fact I am fond of gloating time and again. You have succeeded in escaping the miasma of a kosher, lambish, small town, respectable existence, striking out for yourself instead with the result that you are now somebody, a self-supporting (both materially and mentally) young woman . . . I am proud to think (or maybe I flatter myself) that I had something to do with your decision to quit Savannah. It was I who gave you that initial impetus, that will to change and to dare . . . I am immensely interested to read your rendition of life among the artists.”

Philip Greenberg/Rann would soon change his name again to Philip Rahv, and cofound Partisan Review in 1934; it quickly became one of the most famous and respected literary magazines of all time. The renowned poet T.S. Eliot described it as the best American literary periodical. It featured works by such literary lions as Dylan Thomas, George Orwell and Saul Bellow.

Table of Contents of the Partisan Review. Photo Credit: Larry Petroff

After an affair with the writer Mary McCarthy, Rahv married a friend of hers from Vassar College, the moneyed daughter of a Junior League founder. His second wife was a descendant of John Jay, first chief justice of the United States. One critic reported, “his two wives were extraordinarily similar . . . both quite handsome, extremely WASP, and quite rich . . . and they were both completely un- intellectual and unliterary.”

I considered Ethel lucky to have escaped the fate of the writer’s subordinate wife, a role he was already asking her to play: “I would like you to preserve these letters because I myself do not leave a copy for myself.” But I also could imagine that what attracted her to Philip, and what she passed on to me, was the thrilling prospect of living among intellectual and artistic men and women. My father, a Russian-born intellectual, also drawn to literature and the arts, enabled her to live that life after her romance with Philip ended.

The realization that I will most probably never find her letters has cast a veil of sadness over my project from beginning to end. Based on what he writes, she must have provided him with emotional support and a sounding board at a vulnerable time in his life, in a new country when he had no friends or family to confide in. He described himself at one point as “a very sad, determined young man with a superiority complex, like a hard crust, covering all of my inner self.” He let Ethel see that hidden self.

What he did for her was transformative, as he was the first to say. He gave her the encouragement she needed to leave Savannah and to envision the intellectual world that lay beyond its confining boundaries. The cultured, sophisticated woman she became, and who reared me, was in part his doing. Through her, some of Philip Rahv’s legacy lives on in me. ![]()

An extended version of this essay appeared as A Young Communist in Love: Philip Rahv, Partisan Review, and My Mother in the Georgia Review, Winter 2014. I appreciate their permission to reprint parts of it here.

Doris Kadish. Photo Credit: Larry Petroff

Dr. Kadish donated the Ethel Richman (Young) Philip Rahv (Greenberg) correspondence on May 8, 2013 to the Harry Ranson Center at the University of Texas, the largest repository of American literary archival materials in the country. She restricted access for 10 years while she was writing about the letters. She has since lifted that restriction.

Doris Kadish, Distinguished Research Professor Emerita of French and Women’s Studies, began her academic career in 1971 at Kent State University in Ohio, which she left to assume the position of Head of Romance Languages at UGA in 1993. She also served as interim director of UGA Women’s Studies Institute and Director of the Center for Latin and American Studies.

Philip Rahv Co-founder of Partisan Review

Philip Rahv was Professor of American literature at Brandeis University from 1957 to his death on December 22, 1973, in Cambridge, Mass. The final year of his life was a bitter one marked by inactivity, sickness, self-destructiveness, and thoughts of death. He grumbled that he would be forgotten, but he was wrong. After his death on December 22, 1973, a lengthy obituary by Mary McCarthy, Philip Rahv, 1908-1973,appeared on the front page of the New York Times Book Review. Rahv named the state of Israel as the chief beneficiary in his will.

For a fascinating look at Rahv and the many famous writers associated with Partisan Review, Dr.Kadish recommends “Partisans: Marriage, Politics and Betrayal Among the New York Intellectuals,” by David Laskin.

Dr. Kadish’s nephew David G. Barnet assisted with genealogical research. He consulted census, immigration, and naturalization records as well as information from an extensive range of contemporary newspapers in New York, Savannah, and Portland, Oregon. He obtained Rahv’s will from the Cambridge, Massachussetts, probate court. Doris went to Savannah to interview relatives and members of the Jewish community, to visit synagogues and places her mother had lived, and to find materials and oral histories from the 1920s. She also studied the Partisan Review archives at the UGA Main Library, and did extensive work in secondary source material, including a Ph.D. dissertation on Rahv. She has made some corrections to the Wikipedia entry for Philip Rahv and still has a lot of work to do there.

What’s in a name?

When Larry came to photograph Doris at the UGA library, she noted his Russian sounding name and asked if his ancestors were from the Ukraine as hers were. Yes, they were but their name wasn’t Petroff; he doesn’t know what it was. Larry related that they came by the family name in an unusual way. His grandfather emigrated to the U.S. in the early 20th century, working as a carpenter with a Russian circus. The circus ultimately went broke and left him stranded so he made his way to Pittsburgh to apply for a job at a steel mill. When the foreman began calling out names of who they had hired, they did not call his name. “When they called “Petroff,” there was no answer…so my grandfather raised his hand and got the job and the name.”

When Larry came to photograph Doris at the UGA library, she noted his Russian sounding name and asked if his ancestors were from the Ukraine as hers were. Yes, they were but their name wasn’t Petroff; he doesn’t know what it was. Larry related that they came by the family name in an unusual way. His grandfather emigrated to the U.S. in the early 20th century, working as a carpenter with a Russian circus. The circus ultimately went broke and left him stranded so he made his way to Pittsburgh to apply for a job at a steel mill. When the foreman began calling out names of who they had hired, they did not call his name. “When they called “Petroff,” there was no answer…so my grandfather raised his hand and got the job and the name.”

Larry retired in 2011 as a civil engineer with a petroleum company. He began taking photographs as a hobby while in the army in the late 1960s, and since retirement has taken numerous photography courses.

The comments are closed.

Reader's Comments

Fascinating article, Doris!