The one certainty in life is that it never stands still. Events and seasons always move forward, and aging is the inevitable byproduct of a world in motion. While some get swept away in the current of time, those who aim to live with purpose and passion find a way to create a life of beauty. Like any worthwhile pursuit, the art of aging takes effort, but those who make a well-crafted life a priority are rewarded with joy and fulfillment.

Chip McDaniel, 84, has spent decades perfecting the art of living. A naturally creative person, McDaniel will dabble in anything that catches her eye. Taking what she calls a “leap of faith,” McDaniel retired at 52 from her position as Communications Coordinator for Westinghouse in Athens. Her intention was having freedom to do the next inspired action.

“I wanted ‘living itself’ to be an art form,” says McDaniel.

From building to blogging, McDaniel creates and recreates. She has composed music on her Yamaha electric keyboard, and designed album covers to depict them. Her artistic tools include everything from saws to computers. There is virtually nothing that McDaniel will not look at with a creative eye and the delight of an artist.

McDaniel says the art of aging isn’t about pursuing greatness but finding contentment. “I think it’s about a style of living that’s fulfilling. I’ve been drawn to the ‘art of living’ as a philosophical approach.”

When it comes to putting together the composition of a well-lived life, McDaniel says she asks herself three questions about every endeavor: Is it satisfying? Is it fulfilling? Is it meaningful?

“Also,” she says, “do what you love and that will be enough.”

Watch more of Chip’s musical compositions »

Don Hunter, 72, has found that what he loves doing is photographing nature. A natural extension of his 33-year career as an environmental scientist with the U.S. EPA in Athens, taking pictures of southern flora during Nature Rambles at the state Botanical Garden led Hunter to specialize in capturing images of local pollinators for documentation by UGA.

Like most people, Hunter had taken pictures all his life, but he says it wasn’t until after he retired that he got interested in the art aspect of photography. While he finds beauty in nature and satisfaction in the creativity of photography, it is really the science that drives Hunter’s craft.

“There is a personal satisfaction in knowing my work is useful and appreciated. I get a range of quality. Sometimes I get photos that are barely good enough for documentation.”

However, there is an enthusiasm for the art that ignites a spontaneous joy.

“But I’ve also come up with blow your mind from a beauty standpoint. The plant and the bug are lit up so well I just think ‘My, gosh, I couldn’t have done it if I’d tried!’”

A sense of worth and the spark of discovery motivate him to continue photographing every day.

“The diversity and beauty of the different critters inspires me. Not knowing what I’m going to find when I walk into a meadow… it’s exciting to me to come across a new beetle or a new bee. And to get a really good picture.”

See more at facebook.com/don.hunter.56/photos.

Rosemary Woodel, 80, says her initial interest in photography was born of necessity.

“After my divorce, I needed to fill the walls!”

Although not a trained artist, she says she has always had an eye for composition and design, but as an office manager at the university, art was mostly peripheral in her life.

Now, without art, says Woodel “there is no way this would be any kind of life worth living. I’m so glad I have paintings and photographs and that I can enjoy hearing and listening to music and singing.”

Although she loves and values beauty and creativity, she says, “I didn’t take it seriously as an artist until ten years ago.”

That’s when she began taking classes in writing, photography and alcohol ink at the John C. Campbell Folk School in North Carolina. She found that she loved digital photography classes and that she had a knack for capturing a moment.

“I’ve gotten into art shows and I sell my work,” Woodel says. “It’s nice to know you have photographs worthy of other people seeing.”

Another advantage to Woodel’s art she says is that it documents life and provides a canvas for reflection.

“I don’t have a great memory so photography and making movies are my external hard drive. If I forget—I know when; I know who; I know where. It’s a great memory bank.”

Recently, eye problems have affected her life and her art, but Woodel continues to adjust and enjoy her artistic pursuits.

“I still take the pictures I can and make them the best I can.” Lately, she’s pivoted from still pictures to video. “When I discovered the creativity around me [at Talmadge Terrace Independent Living] – music, writing, decorating—I started making a series of movies to document that.”

“It’s all about experience and just trying it,” she says of the community’s ukulele band out serenading the rescue animals at Sweet Olive Farm.

“I hope when I make movies it inspires others to be more creative, and I hope my movies make people feel better. I want them to bring joy and to emphasize community.”

See Rosemary’s other movies on her YouTube channel.

Watercolorist Par Ramey, 71, finds refuge in her community of fellow artists. She had enjoyed many diverse occupations, but when she was widowed in 2004, she turned to art for comfort and community.

“The Lyndon House staff was so welcoming I basically moved in down there. It was a way to adjust to widowhood.”

A native of Athens, Ramey was influenced by her grandmother who had moved to New York during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1930s. As a girl, she spent summers there where she had freedom to explore art and was exposed to the work of successful black artists. She recalls it was a respite from the segregation she experienced at home.

“In Athens you didn’t hear about black artists. They were around, you just didn’t hear about them because they weren’t publicized. I lived for the summers when I could go there. It was like Harriet Tubman had taken me to freedom.”

Ramey settled in Athens in 1979 and raised her family here. When she lost her mother, her sister, and her husband in the same year, she was faced with devastating loss and a difficult transition.

“I had to do something to deal with that. The Lyndon House [Art Center] was a sanctuary for me. I went there to heal. Seeing, hearing, eating art, I wanted to be a part of that world. I’d just gone through the saddest times, but I found a place to be happy, and I’ve managed to stay happy.”

In the beginning, says Ramey, “I just wanted to paint a pear.” Now, however, she has turned more to self-reflection.

“I love painting nature, fruit, animals, weather, trees, but now I want to do more abstract and go deeper into the emotions. I want someone to look at my paintings and be captured by them, not to just move along. I want them to see something. I want them to stay there and figure out what’s going on. That’s what I like about abstract—it’s not just flinging paint but flinging emotions.”

Life is like art, says Ramey. “When I started this journey, I was 55, and there has been a lot learned. I became this artist and new experiences came with it. It was empowering.

Jack Eisenman, 79, recalls a defining moment when he discovered power in words. A retired Army colonel at his junior high school scared him to death. That is until he started quoting poems.

“He would do that about once a month. I always remember that and credit him for first exposing me to poetry.”

During his education and subsequent career as a member of faculty at Palm Beach Atlantic University, Eisenman says he wrote no poetry. Once retired, he knew he wanted that to change and was committed to writing the best verses possible.

“I joined a group and attended workshops.”

Not only does Eisenman create poetry with words on paper, but there is poetic beauty and graceful humor to his style and habits. In the fashion of a 19th Century poet’s garret, Eisenman outfitted a writing room where he steals away to create.

“Everyone needs a private space no matter what they do,” says Eisenman. “You have to climb a ladder to my poet’s garret. It’s where I come to be creative.”

Eisenman says he is a firm believer in the power of the muse. Interacting with a yellow pad before he goes to a computer, Eisenman allows words to flow directly from his hands to the page.

“I don’t necessarily have a topic in mind, but before you know it the muse takes over. Sometimes the poem writes itself, but there are other times that I am intentional and philosophical.”

However, he says, “Every poet wants to be read. I hope those who read my poems can say ‘I get that’ or ‘I experienced that.’

Eisenman says he never considered himself an artist before becoming a poet, but after 15 years he believes he’s found his groove.

“I think I’ve found my voice.”

POEMS BY JACK EISENMAN Box of Toys Whose hands packed the arm-less doll, Ford truck with rust-locked wheels, Bag of marbles, broken crayons, coloring books Where dogs are blue, lines irrelevant? Judy’s Swing The entire Bailey Street 300 block had swing envy of the girl two doors down from 319. Kids came from as far away as 387 to stand in line for a one-minute float through the sky, soaring so high toes brushed leaves on the lowest maple limb which must have been twelve feet from the grass but seemed Jack in the bean stalk high. Every kid anticipated the grand climax, the jump. The jump, a leap of faith that between letting go, flying through the air, and hitting the ground eight-year old’s lives would not flash before them.

Read more of Jack Eisenman’s poems.

Cheri Wranosky’s artistic voice finds expression in three-dimensional form. Found objects spark her fancy. As art director for the UGA Alumni magazine, it was natural for Wranosky, 74, to enjoy artistic activities in retirement.

“It just gives your creative mind something to do besides thinking about the world and your own problems. It calms you. It’s something to concentrate on and lose yourself in.”

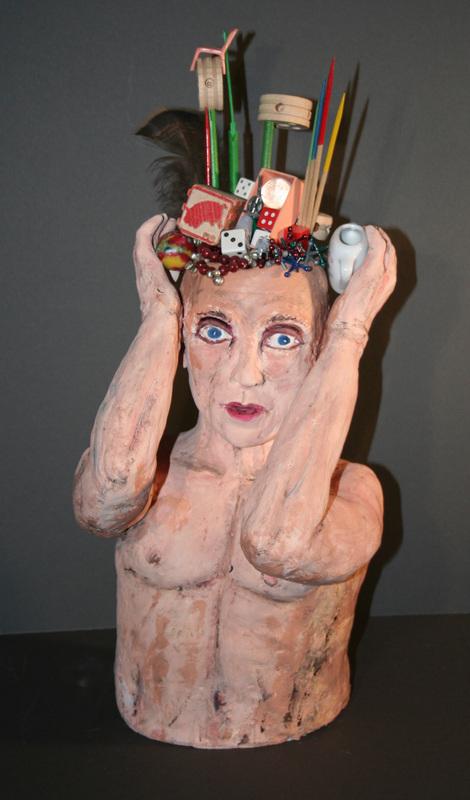

Classes at Good Dirt launched her into sculpture. Inspired by found objects and things that she has collected, her art often reflects what life brings her way.

“I used toys from my mom’s house on the head of one of my pieces ‘Toys in the Attic.’”

Wranosky hopes that her pieces will influence others by giving them something to ponder.

“I hope they puzzle over it. Some people love it, and some people hate it, but I hope they take away some fun—a lot of my art is whimsical.”

In some ways, Wranosky’s art mimics the progress of life.

“I started just doing little figures,” she says. “I had to learn how to make an ear. Some sculptures were just figuring out how to do it.” But now she says, her art is about more. “Now they need a message.”

Having successfully learned “how to do it,” Wranosky’s art has had significant exposure locally, around Georgia, and out of state. Her work has been featured in magazines, a textbook for young students, and the book, Best of America: Sculpture Artists and Artisans.Recently Wranosky has taken her art to a new level making paintings of her sculptures.

“I’m shifting a little to 2D. In that format you can add a background that you think the sculpture should have been in. I think it changes the message a little, I really do.”

See more of her work at www.cheriwranosky.com.

Using fabric as a medium, quilter Scott Mason makes art that blends two- and three-dimensions.

He says of his art, “I’m in it for the unique things you can do with cloth. Sewing is engineering with soft materials.”

Mason, 78, who retired from a career in marketing research, says he sees fabric as another medium for building.

“You can hang it, put it on the bed, cover your lap. It’s a very practical art.”

Fabric is more accessible too, says Mason. It’s readily available and easier to manipulate than wood or metal. “Quilts can be easy,” says Mason, “They are cloth, but they can also be high art.”

Inspired by the expansive and active quilting community in Bend, Ore., where he had a seasonal home, Mason was inspired to take a quilting class. He confesses that he was a difficult student, insisting on creating designs from his own imagination.

“I push myself and try to do more creative things, my creative things, and not to be happy with what other people have done. I find that so much more fulfilling.”

Did he ever feel self-conscious about taking up a traditionally female craft?

“’Women’s hobbies’ and ‘men’s hobbies’ seems a pretty artificial distinction. I do what interests me, and there’s a lot about quilt art—design, technique, and possibilities to keep a woman or a man engaged for a lifetime.” More than that. “There is pleasure in the peacefulness of assembling quilts and the real art to life is how at peace you are with yourself.”

Retired health care consultant Beth Warner, 65, has become a master at crafting a peaceful life. She is determined to find beauty.

“You can choose to seek out beauty wherever you are,” says Warner. “You just have to see it.”

Now a farmer and shepherdess, Warner says that she has always been a nature lover. She admits as a child she wore her mother out with her enthusiasm.

“I would rush into the house begging my mom to ‘come see!” some exciting thing I’d found. When she’d get out there it would be a leaf.”

Although Warner is skilled at drawing and painting, her desire is to use the bounty of her land to create. One skill Warner plans to sharpen is felting the wool she collects when shearing her sheep. As a student at the John C. Campbell Folk School, Warner learned about eco-dying.

“Wool plus plants, plus mordant, plus water, plus heat, plus time, equals magic,” she says.

Much of Warner’s art is never seen. “Sometimes when I walk, I create art at the base of a tree. I know no one will see it but God. It’s sort of an offering.”

She will collect leaves and arrange them in patterns on a table knowing they will soon be swept away. Fortunately, Warner has embraced social media to preserve her transitory art. A skilled writer and photographer, she journals on platforms like Facebook to share and connect.

In the last year, Warner has lost six friends to circumstances as diverse as accident, Covid and suicide. A quote from her journal explains how she moves forward through grief.

“I find myself longing to create. To give life to the ideas that are simmering inside. To bring forth beauty from nature.”

Like life, much of Warner’s art is temporary and many of her creations will fade away. But she wears the graceful flow of age comfortably like a hand-felted shawl, and her example of living beautifully is an inspiration that will linger.

Growing old takes no finesse. It happens without any interference. But aging with flair is an act of art and requires attention to detail. The one thing Boomers who understand the art of aging have in common is that like a watercolor, poem, quilt, sculpture, or photograph, they bend life to their vision. They seize every moment and capture joy.

Kelly Capers is a freelance journalist who enjoys the art of aging by writing for Boom Magazine.

MORE ART! Oconee Cultural Arts Foundation (OCAF) regularly has annual members’ only shows which guarantees submissions will be exhibited. The 2021 Members’ Show is open to the public through July 16. Jack Eisenman has organized a senior group called Poets of Winterville, which will have its first in-person meeting of 2021 on Thursday, Aug. 5 at 1 p.m. at the Winterville Center for Community and Culture. Adults over 55 can join before the end of July and have their first-year annual membership fee waived. For information, email poetsofwinterville@gmail.com. With the help of a grant from the Athens Cultural Affairs Commission, local artist Shirley Chambliss interviewed and recorded interviews with four local artists, including Abraham Tesser (wood), Caroline Montague (clay, sculpture), Mary Mayes, Clay and Cameron Hampton (various). Enjoy the “Getting to know you” interviews.

** Editor’s note: Since we wrote this story, other media have been talking about the positive impacts of art and creativity on healthy aging. A recent Washington Post story features retirees who’ve entered a much different second act. Matt Fuchs writes, “Ongoing research suggests that creativity may be key to healthy aging. Studies show that participating in activities such as singing, theater performance and visual artistry could support the well-being of older adults, and that creativity, which is related to the personality trait of openness, can lead to greater longevity.

And the current AARP Bulletin includes a story about retirees who’ve become successful artists and found that the “creativity and the passion to express it were always there; they just lay dormant, waiting for the right time to emerge.”