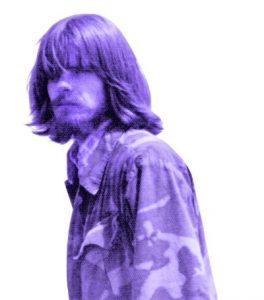

Photo of Bob Kobres

This year marks 50 years ago that a ground-breaking musical opened in New York. Staged in the Public Theater by Joseph Papp, the producer of the Shakespeare Festival, “Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical,” was a far cry from Elizabethan theater. Hair wasn’t a usual topic for musical theater, but in this case it took center stage as a symbol of generational, cultural and political divisions in a turbulent time for America.

The play’s sometimes obscene language, easy acceptance of drug use, protest against the Vietnam war, and free-wheeling attitude toward sexuality seemed scandalous to many Americans. But, the play was a breath of fresh air to some of a younger generation who sought release from what they saw as the buttoned-down drabness of their parents’ post-war lives.

Walk across the UGA campus these days, and no one seems to notice or care about the variety of hairstyles on male students and staff. But many of the men who lived through the tumult depicted in the musical have vivid memories of how they were judged by the way they wore their hair, and the clashes that could break out between the “freaks” and the “straights.”

For some, the stereotypical beliefs about what hair meant were true. John Gingerich, 67, an artist and occasional model, said, “I’m an old hippie. I went to Woodstock. I’ve always lived sort of out of the mainstream.”

Gingerich, a slim 6-foot-4, has long, curly red and gray locks down to his shoulders and a red beard.

“I haven’t shaved since 1972,” he said, and the only times he’s cut his hair since then are the half-dozen occasions when he donated it to Locks of Love, a charity that collects hair to be made into wigs and hairpieces for children with medical hair loss.

He recalled one time when he applied for a job with the post office, met all the qualifications and was on a list of acceptable applicants, only to be told by a supervisor that he wouldn’t be hired “looking like that.” Only after a union representative intervened did he actually get the job – and keep the long hair and beard.

Gingerich said the way he wore his hair wasn’t so much a political statement as a preference for naturalness and ease of maintenance, but for many African-American men in the 1960s, a hair style was both a protest and a declaration of identity.

“In the 1950s, and into the early ’60s, it was ‘fried, dyed and laid to the side,’” said Charlie Maddox, 70, a minister and veteran civil rights activist, referring to the “processing” of hair to make it straight. By the mid-’60s, though, many younger black men adopted the afro, a more natural style that could crown a man’s head with an impressive wreath of hair.

“At first, that was seen as defiant and threatening, even by some people in our families,” Maddox said. Many older family members thought it was dangerous for young black men to stand out too much and call attention to themselves,” he explained.

Photo of Charlie Maddox

For white men, having long hair often was seen as rebellion against their fathers. The shaggy Beatles cut Bob Kobres wore in the 1960s caused friction in his family and Gingerich’s father told him many times he needed to cut his hair.

Kobres, 69, and now retired from the UGA library, also butted heads with his military bosses. He once got into trouble when he was in the Air Force for not keeping his hair cut as short as regulations required. He challenged the requirement, prevailed, and when he got out of the service, he let it grow – since then he has worn it long. Now he wears his white hair either in a ponytail or gathered into a bun.

“It’s a little bit of a statement of independence, to some degree,” he said, but it’s also easy to deal with. “I don’t have to do much to it, just wash it and dry it, and it’s fine.”

While Kobres and Gingerich have worn their hair long for decades, for many men, including Maddox, it was a short-lived choice. “In the world of work, it was frowned on,” he said, so for the last 40 years, he’s gone to the same barber and had the same close cut he sports now.

Hairstyles these days aren’t as likely to lead to conflict as in the ’60s, but still, “it’s interesting to see people react differently if you’re older and have long hair,” Kobres said.

“It startles some people,” Gingerich said. “They think of Santa Claus or a biker, even though I’ve never ridden a motorcycle in my life.”

So, just as much of the music of “Hair” continues to sound contemporary, it’s worth remembering that a man’s hair choices still can have meaning in lots of ways.![]()

Changing hairstyles put lots of barber shops out of business

Young white men with long, flowing locks and young black men with afros had a big impact on the business of barbering. An industry group says 20,000 barbers left the field in the 1960s and ’70s.

Herschel Reeves began working in 1948 in his father’s 10-chair shop when haircuts were 35 cents. He himself had a five-chair shop in Five Points that too diminished once rebellious young men began growing their hair.

“It put a lot of barbers out of business,” he recalls, noting that men turned to women stylists to trim their hair in what became known as unisex salons.

African-American barbers Homer Wilson, 70, and his brother Talmadge, 61, have seen their business change also. Like Reeves, they learned their trade in their father’s shop in downtown Athens. Homer began barbering in the ninth grade while Talmadge shined shoes in the shop in the fifth grade.

“We did processing to relax the hair,” Homer recalls, “then we would do individual finger waves or S-curls.” The afro changed all that, although it did require some maintaining, he says, using chemicals or heat for blow-outs.

Today, “everybody wants to be different,” Talmadge says. “Afros, boxes (once called flat tops) and fades (the military’s ‘high and tight’). And now many want color, sometimes three colors, but neither man does that “because it takes too long.”

And when the talk in an all-male gathering gets boisterous, Homer says he yells, “fellas!” and Talmadge says loudly, “How ’bout them Dawgs!”

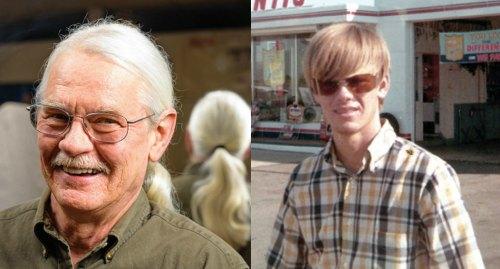

Bill Griswold, retired UGA journalism professor, Then and Now.

After two years in the army, having to get a white-sidewalls haircut every week, when I got out I swore I ‘d never cut my hair again. And that vow held through two years of college, a job at a radio station in Atlanta, and then a fall and winter back in Columbus GA. By that summer, it was too hot to have a mop of insulation on my head, and since then I’ve had normal, medium-length hair — thought it does get shaggy sometimes, because I still hate getting haircuts.

The comments are closed.